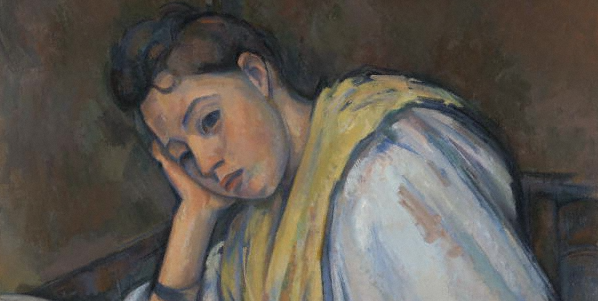

Guilt & Shame

‘Where guilt is usually thought to be an internal experience, characterised by hearing the voice of conscience, shame is more often linked to a feeling of social condemnation and the horror of being seen.’

– Tiffany Watt Smith in The Book of Human Emotions: An Encyclopaedia of Feeling (2016)

An extract from Ill Feelings by Alice Hattrick (2017)

“Shame, a consequence of my illness, and its cause, is what made me want to disappear, to become invisible (like my illness) to those other children at school, the ones who I thought didn’t take me seriously, who compared me to objects, but also those who insisted my ill feelings were not real…

If illness is a source of shame, expressing it is nothing to be proud of. But shame can be a valuable emotion. It is proof that you are living a disapproved life; a sick life. I felt shame when I made myself visible to others who refused to see me as anything other than a problem – as someone who did not fit in to the world of the healthy or the sick. As a child, I felt ashamed that I was not ill enough.

[…] I associated pain and fatigue with the loss of myself, of my personhood, because, for a long time, illness, for me, meant failure. A failure to process information, to speak clearly, to concentrate long enough to read, and write.

In her essay ‘On Being Ill’, Virginia Woolf describes how writing the experience of ‘common illness’ contains a political power. We live through our bodies: ‘Literature does its best to maintain that its concern is with the mind; that the body is a sheet of plain glass through which the soul looks straight and clear.’ ‘On the contrary,’ Woolf reminds us, ‘the very opposite is true’. Illness is something we all experience but don’t often read. Woolf calls for a literature of the ‘daily drama of the body’; we need a ‘new language’ for pain, she writes from her sick bed, one that is ‘primitive, subtle, sensual, obscene’.

[…] In her 1978 book Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag warned against using metaphors for illness, because it fosters feelings of shame in the sufferer, and a culture of victim blaming. Physical symptoms reflect the sufferer’s character, so much so that the character is thought to cause disease, or inhibit its cure. Sontag cites, among others, Katherine Mansfield, who, dying of an advanced lung disease, wrote in her journal: ‘The weakness was not only physical. I must heal my Self before I will be well.

[…] Illness can fill you up, until your sense of self is defined by it. It makes you feel like a fake and a fraud. It shames you into difference. If chronic fatigue and pain are much like shame, they also affect how you perceive yourself, as a person with a body. Ill feelings make you both impressionable and hard. To stop yourself feeling suddenly diffuse, as if you are disintegrating, you make yourself small and solid – impenetrable. You appear self-contained because you spend most of your energy trying to hold all the parts of yourself together. Illness made me guarded, quiet, small, contained, like Louise Bourgeois, who wrote, ‘And what’s the use of talking, if you already know that others don’t feel what you feel?’’’