A dialogue must take place, precisely because we don’t speak the same language.

As we struggle to come to terms with a world in crisis and imagine more inclusive, equitable and environmental futures, the limits of our own cultural reflexivity stare us in the face. “Language is the house of power,” Mustapha Khayati writes in Captive Words (1966), warning us of the pitfalls that come from critiquing the old world in the very language it was made. Prompted by the question “What do we have in common?” we take differences not as a force that pulls us apart, but as a starting point for coming together.

In fact, what is in common always only emerges in translation—the translation between different experiences, interests and subjectivities. Translation occurs at the intersection of differences, not their convergence. Thus, rather than aiming for a precise mirroring of language that would imply the erasure of difference, translation is founded on and sustained through differences. Similarly, commoning understood as an ongoing social practice also depends on the encounter and negotiation of difference. Commoning is never free of friction. Accordingly, Stavros Stavrides argues that commoning can only exist as an ever expanding endeavor that welcomes newcomers (Stavrides, 2016). Newcomers play a key role in challenging the common and shedding new light on habits and relations. At first, their view points might be unsettling, especially when they unmask common rituals or prevailing power structures. Meanwhile, the distance their language creates can also be enabling and heighten a sense of agency: the process of literally coming to terms and building mutual understanding requires active participation in defining common ground. Vilem Flusser argues that being unsettled is indispensable for settling with resolve (Flusser, 2003: 25-27). So, just as there are ‘no commons without commoning’ (Linebaugh, 2008: 44-45), the encounter of and translation between differences is an ongoing social practice on which the sustainbility and resilience of a community paradoxically depend. In contrast, if shared interests, beliefs and habits are merely passed on, a community soon calcifies and will often risks the accumulation, even abuse of power. In communities devoid of differences the common may become an instrument of control or policing. Jaques Rancière, as referenced by Stavrides, describes how if ‘police’ defines community ‘as the accomplishment of a common way of being’, ‘politics’ conceives community ‘as a polemic over the common’ (Rancière 2010: 100). Commoning is inherently political, as it emerges from the agonistic encounter of diverse and pluralistic voices. Accordingly, a polemic over the common and the pursuit of the question ‘What do we have in common?’ requires us to find a common language without reducing our differences to a common denominator, but by celebrating them as the foundation of other possible worlds.

Here, we aim at initiating a dialogue about spaces and practices of commoning, their situated histories and diverse etymologies, and the (im)possibility of translating them from one language or culture into another. If indeed other worlds are possible, they will emerge from a plurality of practices and viewpoints, old and new, indigenous and urban communities, feminist and environmental movements alike.

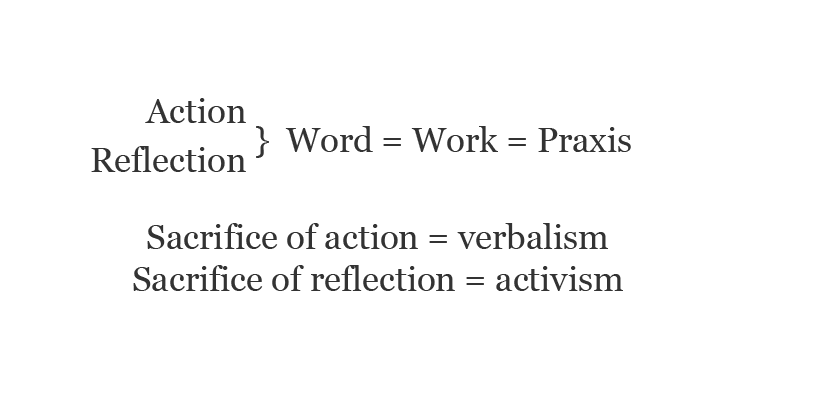

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), Paulo Freire reflects on the notion of dialogue or the dialogical as both “reflection and action, in such radical interaction that if one is sacrificed—even in part—the other suffers immediately.”

He insists that “while to say the true word—which is work, which is praxis—is to transform the world, saying that word is not the privilege of some few persons, but the right of everyone. Consequently, no one can say a true word alone—nor can she say it for another, in a prescriptive act which robs others of their words.” Any dialogue, then, is marked by humility, the willingness to unlearn and be displaced. Building on Paulo Freire, a dialogue must take place about language through which we describe practices of commoning in order to undo an Anglo-Saxon epistemology of the commons debate and reflect on the entanglement of power and knowledge at the root of contemporary research, education and cultural production. Through these conversations, we hope to explore the pluriversality of commoning, as well as the pluriversality of spatial practices.

Text by Stefan Gruber

Notes

– Khayati, M. (1966) Captive Words: Preface to a Situationist Dictionary in Internationale Situationniste #10 March 1966; trans. Ken Knab.

– Peter Linebaugh. (2008). The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All. University of California Press.

– Rancière, J. (2010) Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics, London: Continuum.

– Stavrides, S. (2016). Common space : the city as commons. Zed Books.

– Flusser, V. (2003). ‘To Be Unsettled, One First Has To Be Settled’, in The Freedom of the Migrant – Objections to Natiionalism, ed. Anke K. Finger. University of Illinois Pres; trans. Kenneth Kronenberg.

– Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). Continuum.

People

Stefan Gruber, is an architect, urban designer and Associate Professor at the School of Architecture of Carnegie Mellon University. He is a co-curator of the ifa-exhibition An Atlas of Commoning in collaboration with ARCH+ and guest editor of eponymous publication, and co-author of Spaces of Commoning – Artistic Research and the Utopia of the Everyday. His native languages are German and French.

Chun Zheng, is a landscape architect, urban designer and PhD researcher in the School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University researching practices of commoning and urban agriculture in the US and China. Her native language is Mandarin.

Helen Young Chang, is a writer, art critic and translator. Her native languages are English and Mandarin.