Deschooling: climate and art

5. Mineralizing land and fabulating climate

Conversation with Nolan Dennis, artist

Dineo Seshee Bopape, sa___ke lerole, (sa lerole ke___), 2016 (installation view, Art in General, New York, 2016)

In an article about how climate change has already transformed everything about contemporary art, William Smith suggests that “framing the climate as a distinct concept for art, another notion to explore, creates an illusion of intellectual distance. But the reality of climate change isn’t a topic for some art to address; rather, it is a historical condition that informs all contemporary art.” Trying to put forward a critical methodology for grappling with this condition, he turns to “ecocriticism” which has gained currency in literary studies as an approach for addressing the implications of ecological upheaval.

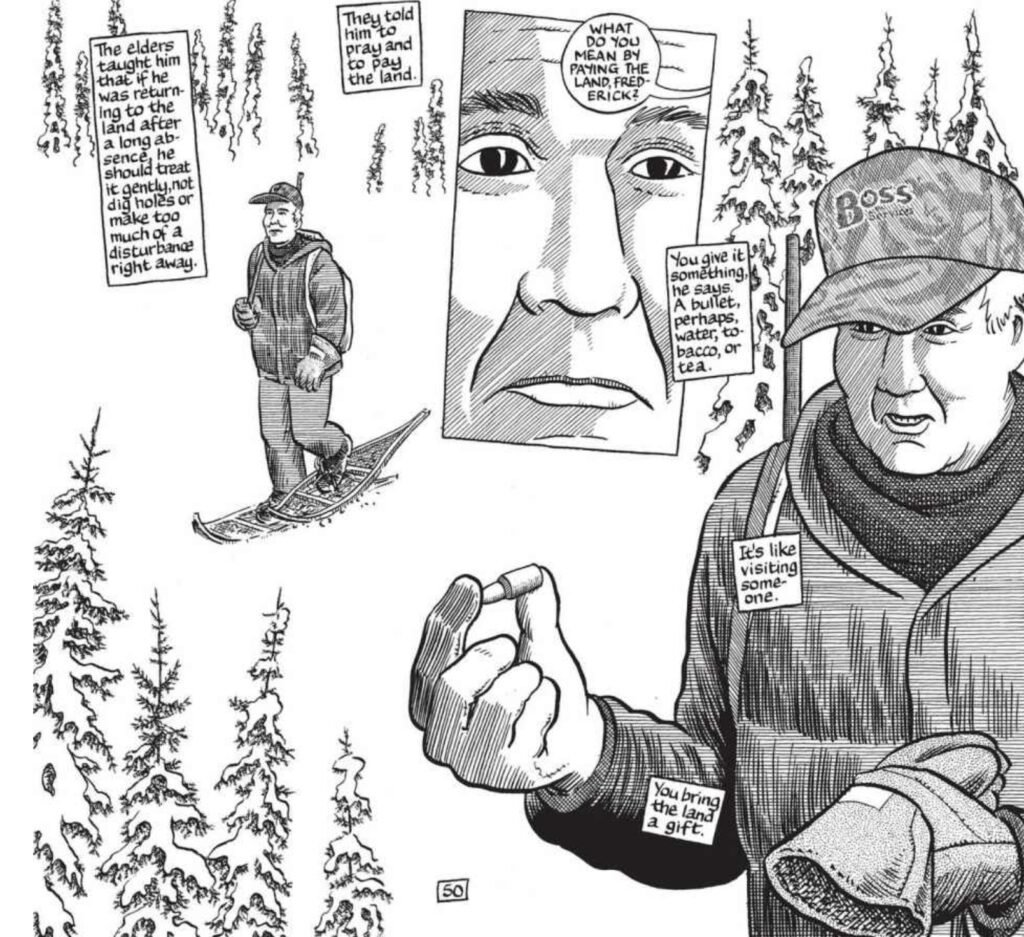

In a similar spirit, I read Paying the Land (2020) by Joe Sacco together with Nolan Dennis, an interdisciplinary artist whose practice explores what he calls a ‘black consciousnesses of space’ or, the material and metaphysical conditions of decolonization. Dennis’ work questions the politics of space and time through a system-specific, rather than site-specific approach, concerned with the hidden structures that pre-determine the limits of our social and political imagination. As such, I was keen to engage with him on this book, a graphic documentation of resource extraction, debt to the natural world and the displacement of the Dene, an indigenous group of First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada.

Excerpt from Paying the Land (2020) Joe Sacco

Reviewing the book, Aida Edemariam summarizes:

“The question that drives Paying the Land is: what do you do? How do you break the dependencies – on oil and natural gas (the ninth largest reserves in the world), on alcohol, on welfare, on an external definition of who you are? Straight compensation and apology is a minimum, and a truth and reconciliation process admitted cultural genocide in 2015, but an influx of cash can be a death sentence to a serious alcoholic. And how do you deal with inevitable change? Nostalgia is no answer; “People have to eat. They need roads and schools,” as one chief, who would dearly like to return his people to subsistence on the land, eventually has to admit. The eternal question about climate change and “progress” applies here too – what is the moral position of denying people things you have already enjoyed yourself, in order to fix the damage that was no fault of theirs? Again and again Sacco finds that “it’s more complicated than that”.

Well, Dennis complicated it even more by making an interesting observation that throughout the book, “land is very rarely spoken about, the conversation is mostly about people”. The image put forward is that the land is inseparable from the people, always something mediated, being acted upon (even if it does act on too). But the land is something that is very rarely encountered as something independent from all this human drama.

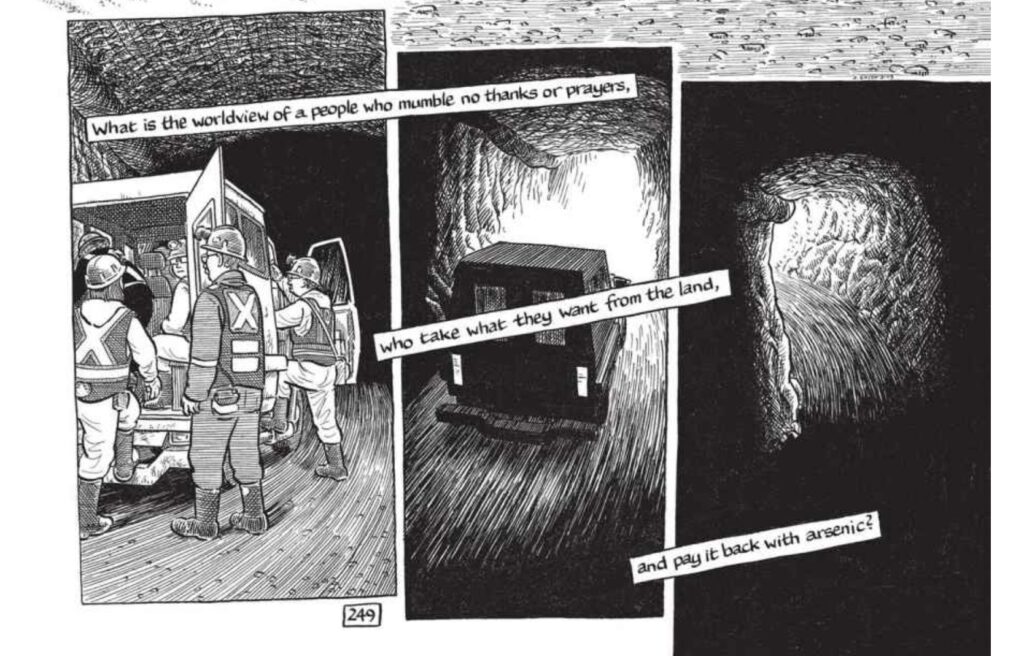

Excerpt from Paying the Land (2020) Joe Sacco

Dennis has an interesting interest in the strange and estranged historical condition of ‘the land’ as a relation that is both imagined and produced, often through alienation from it. “Every time we talk about the land, we talk about it in some kind of productive sense, with an expectation of a value informing the imagined relation, whether that is in agriculture, accommodation, mining.” I was interested in what this dynamic means in terms of treating the land as a resource, after all, whether it be land or sky, wind or water, the same concerns apply to all earth-systems. Relations to those systems are defined by claims to stewardship, ownership and use. I am curious about what informs those claims, in a material sense, recognizing the importance of this to understanding human relations to earth-systems.

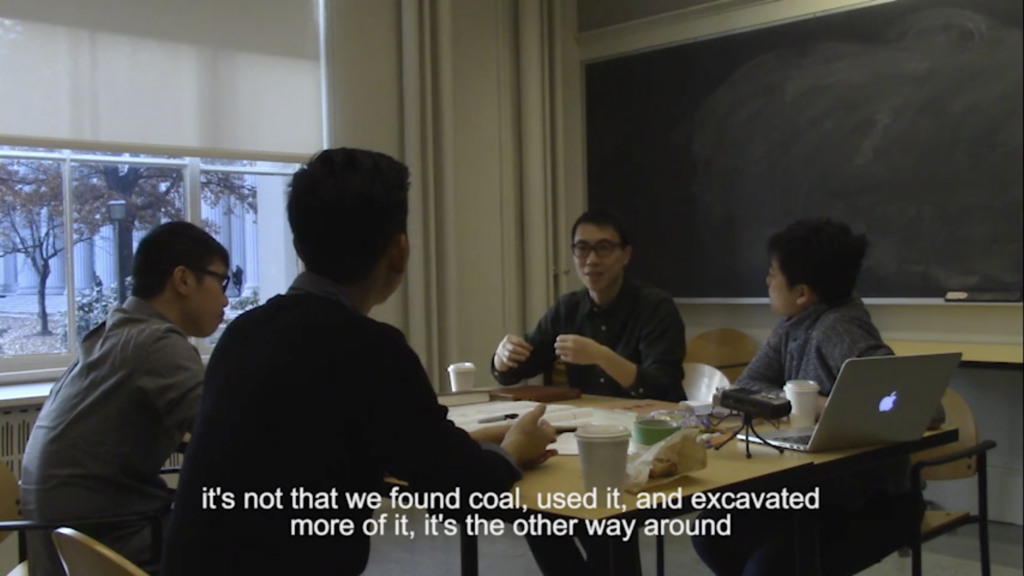

Dennis then cited an anecdote about how during the Meiji industrialisation period in Japan, the environment was worshipped by some as having both personhood and personality, and use of it was conceived os a spiritual practice. This is investigated in a short film Project Lin Daiyu (2017) by Angela Chen (2017) which raises questions about the nature of matter, meaning, and life, all the while interrogates the politics of knowledge production. Bringing together researchers in various fields (visual art, literary criticism, bioengineer, astrophysics), the film asks some interesting questions: “How exactly can matter connote or have meaning? Does if it need to go beyond culture? Does matter influence human consciousness? Does matter itself have its own consciousness?”

Paying the Land focuses on oil being extracted from the land in Northern Canada but in Project Lin Daiyu, coal is the matter in question. One researcher refers to literary critic Hanada Kiyoteru’s philosophy of “mineralism” which called for the rejection of human-centered world views via the elevation of minerals to the top of the hierarchy of matter, since they too have consciousness.

Stills from Project Lin Daiyu (2017) by Angela Chen

Later, I kept thinking about “the eternal question about climate change and “progress”, cogitating about what my own eternal questions are. In the murky space between climate and climate change[1], is there a material consciousness? And if climate change is the ground on which all cultural activities occur, is it not necessary to ask the same questions about climate as Dennis posed in relation to land: how do we construct or imagine our relations with climate? How do we talk about those relations? How do we present them, in art and otherwise?

Here, Donna Haraway and Gilles Deleuze’s use of the concept of ‘fabulation’ offers a useful for tool for thinking about the material messiness of climate consciousness. Haraway’s approach, which she calls ‘speculative fabulation’, is directly concerned with both geohistory and peoples-to-come, a speculative device aiming to shape new ways of ‘worlding’ brought forth by the radical shift imposed by the climate regime: because we need new worldings, new accounts of what we are making to and with the earth, we need speculative fabulation as “multispecies storytelling, multispecies worlding”. Her approach is resolutely materialist, focused not on the earth or land or climate as ethereal or theoretical but as gritty matter, not behold to any conceptual binds.

Deleuze on the other hand claims a more political, philosophical approach to fabulation. Janae Sholtz described Deleuzian fabulation as inventions d’inconnu, inventions of the unknown: where knowledge of the unknown is not ‘discovered’ but that it can only be invented in a kind of fabulation regime, “not predicated on a return to origins or a concept of truth.” Aline Wiame explains that for Deleuze, fabulation does not occur as the myth of a past people, it refuses both fatalism and escapism and “it makes potentialities appear and gives strength to the potentialities it develops.” She continues to show that for Deleuze, “the notion of fabulation gains the leverage of a concept that brings together art and philosophy and impacts the conceptual coordinates of the earth and its peoples”. Or put differently, understanding relations to land and earth systems, “mineralism”, climate consciousness or even the fabulations or art and climate requires a philosophical understanding that “the new earth to be fabulated is an earth for and of thought.” To lean on Haraway’s words: it matters what matters we use to think other matters with; what stories we tell to tell other stories with; what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.

Click HERE to the final text, a compendium of climate consciousness.

References

Cahill, D. (2009) “The Work of Abe Kobo in the 1960s The Struggle for Identity in Modernity; Japan, the West, and Beyond.” Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/151527344.pdf

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Deleuze, G. (1997) Essays Critical and Clinical, trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Haraway, D. (2011) SF: Speculative Fabulation and String Figures, Kassel: Hatje Cantz Verlag.

Haraway, D. (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Sholtz, J. (2015) The Invention of a People: Heidegger and Deleuze on Art and the Political, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Smith, W. (2020) “Climate Change has already transformed everything about contemporary art”. Afrt in America. Available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/climate-change-contemporary-art-1202685626/

Wiame, D. (2018) “Gilles Deleuze and Donna Haraway on Fabulating the Earth” Deleuze and Guattari Studies, Nov 2018

[1] Climate is the average weather in a given area over a longer period of time, climate change is any systematic change in the long-term statistics of climate variables such as temperature, precipitation, pressure, or wind sustained over several decades or longer. This can be due to natural external forcings (changes in solar emission or changes in the earth’s orbit, natural internal processes of the climate system) or it can be human induced. The classical period used for describing a climate is 30 years, as defined by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).