Band of Burnouts

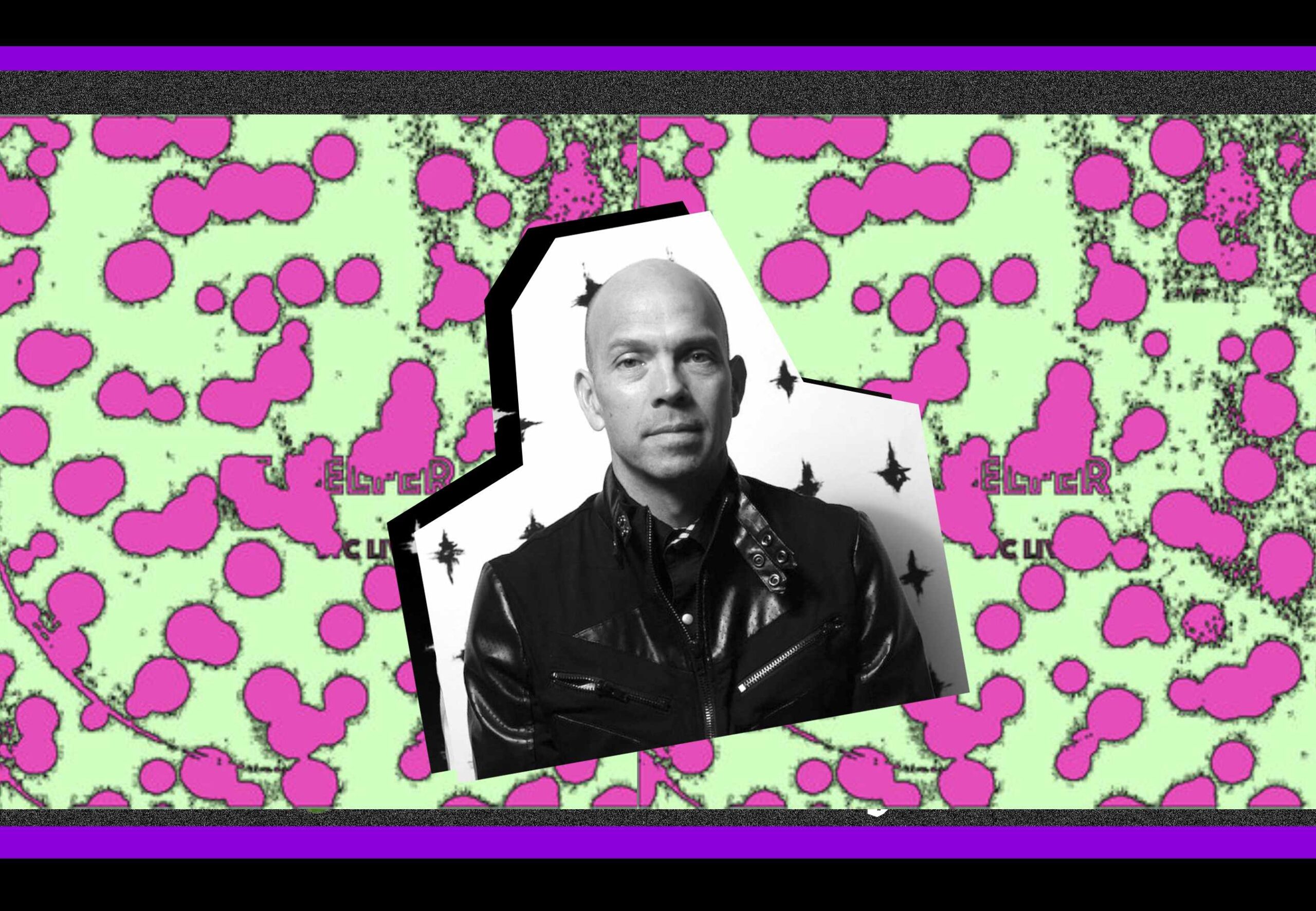

Interview with St. Celfer – Part I.

An interview with Seattle-based musician John Parker, aka St. Celfer, on burnout, homemade instruments, and making during the pandemic.

Hi John. After hearing your musical submission and corresponding about your experience with burnout, it sounds like you have been on quite a journey through, with, and by making music.

You mentioned your burnout was related to your Olympic past. Can you tell us about your athletic life and how you came to making music?

Hi, Jess. I really enjoyed discovering your writing and analysis. Your online magazine No Fun is the opposite of its name and a captivating collection of ideas. I was pleased to find it via the Band of Burnouts project. Considering ‘burnout’ as an ‘idea’ that could expand beyond the overuse of the word struck me. It is enjoyable for me to contemplate something that is an everyday concern in my field of sports and its more profound implications. I was both an athlete and coach at the Olympics. I believe that the term ‘burnout’ in sports has a slightly different meaning than elsewhere. It is more easily understood in the context of physical effort.

As an athlete, I was not the most talented. Slightly smaller, weaker, all fury and emotional energy. I was also a student of the sport (which I later applied to coaching). It was never sustainable, and ‘burnout’ was an accepted outcome… also called retirement. Back then I truly believed it was “better to burn out than fade away”. Fortunately, in sports you are not expected to do it your entire life.

What is different in coaching is that you are in denial of the possibility of suffering from a burnout yourself since it reflects an inability to do your job or lack of ‘care’ for an athlete—especially at the Olympic level.

Perhaps in the past athletes were under the idea that having a burnout reflected a lack of toughness, or a suggestion that one is ‘just not into it’. Now we know that there is a real physical reaction to too much effort without enough recovery. This is supported by data. In fact, I primarily monitor athletes’ recovery and initiate conversations if they are feeling burned out.

Back to your question regarding music making, my earliest memories are of both sports and music. Composing and performing came late and by accident, after many years as an avid fan attending shows, reading zines, buying vinyl, cassettes, and then CDs. I had lived through the Seattle 90s—my first job was there—and was lucky to witness a similar scene budding in Brooklyn during the early 00s when I left my job and moved to New York to become a full-time artist. I bought a laptop and a CD scratcher and started messing around. A highpoint happened at CBGB when I asked the sound guy to plug my computer into ‘his’ PA system. He did not answer and simply spat at my feet. Sacrilege! I had out-punked the punk rock guy at the place where it all began.

Long story short, I ended up leaving New York, disenchanted with the art market. Fortunately, this only affected my desire “to make a living” in the arts and not the actual desire for making things. Really what I was burned out by was the business of it.

With this most recent music you’re releasing under St Celfer, how do you describe your sound? I know you are also making your own instruments…

In all the best ways, the description of my sound is a tagging nightmare. A crashing of neat and tidy labels crushed into digital soup. I have a folk sensibility manifested in electronic sound-making devices. In terms of composing, it is rooted in ideas of free jazz improvisation and experimentation. In terms of performance, I unabashedly hope to have a little emo flair—nothing flamboyant—just a small cathartic release I imagine a blues musician had in their heyday, causing trouble at a small club one hundred years ago.

The instrument is called a “gambiarra” in Brazilian Portuguese and it is homemade. This instrument is meant to be played and heard live.

During the lockdown at the height of the pandemic in 2020, I put together everything I have learned in both art and sport and created an interface for making music—playfully named ‘Step.4D’—a nod to the popular book of the 70s and movie of the 00s. It also references my interest in the 4th dimension. The Step.4D™ is truly live and it has made me feel alive, which is a good thing during a pandemic. I wanted to transition from a studio-heavy process to something more spontaneous. Instead, it allows me to focus on how to react rather than planning and executing. This is straightforward Abstract Expressionist painting theory.

I made the Step.4D™ out of inexpensive things I could buy on the internet, mostly repurposed gear. Even more valuable were the discussions that I had with others (who were also in lockdown) while acquiring the gear, about how to address the dilemmas that arose while patching the instrument together. This unfolded over a few months. It felt like a community event via the internet, as landline conversations used to feel.

To answer your initial question about the best way to describe the music—I use the tag, ‘noise’. It works about as well as John Cage’s 4′33″ being called ‘silence’. True silence is akin to death and is absolutely terrifying. There is a lot of noise today. I wonder if we just need to hear the music within it.

This is an example of a remarkable and rare literal connection between my art and sport. A decade ago, the national sports organization for whom I was working for put me in charge “catching them up” technologically with other countries. I was given a large budget and got all the latest tech gear. It is important to note that this gear was in no way necessary to playing the sport. It was only to gain an advantage in data collection. The result was a substantial collection; yet I ended up using almost none of it because I would have needed a full time assistant just to interpret the data. Technology takes back what it gives. The limiting factor was the interface between man and machine.

You were able to get some traction on Bandcamp for your releases by actively reaching out to Bandcamp itself. How did that go, and do you see music as your main vocation and venture now?

Not so long ago an artist colleague and I were discussing making music for no audience. Would continuing on that path descend into some sort of Unabomber insanity? I am introverted by nature so making music or art and avoiding social interaction is attractive. I’ve realized it is decadent and self-indulgent, too.

Just before the pandemic, I was surprised to have some tracks from an earlier project appear as ‘avant-garde classical’ on Radio Eclectus, a Seattle program curated by Michael Schell. Wanting to stay sane and having zero expectations, I pitched my new tracks to various outlets, took longshots, made a bunch of cold calls. It was equally an exercise in maintaining integrity in the creative process. I don’t make things with the intention to be or become popular. I was surprised when Bandcamp wanted to highlight the tracks.

I sent them a science fiction plot. That I was returning from the future to the second Dark Ages (our current historical period) and had made a post-capitalist instrument that cost nothing to make. In this future, things can be made almost for free (and currency does not exist).

Lockdown afforded me 280 live recordings of which 3 were highlighted by Bandcamp—putting my music next to people who have label support and are much more famous than I. That said, as lockdown is over, the project is over. I have no intention to make music my sole activity since having multiple activities has cultivated my creativity in a balanced way.

Having prior experience with burnout, does it still feel like an imminent risk in your creative work too—or did you feel recovered in a way that wisdom might prevent its recurrence?

I looked up ‘burnout’, thinking that it originated in sports. The definition from the National Institute of Health says it did not originate in sports but rather is first referenced by the medical field. Of course, this makes sense. Now I’m looking into it I am somewhat surprised that it places this ‘state’ as a lesser stage of depression. A driving force in my artistic work is to take on labels like these. This desire to codify and categorize, to box things up… Put a square around it. Anything looks good inside a frame. Have you ever noticed that sometimes the frames in a museum are more interesting than the paintings? This illusion is part of a delusion that is necessary for the upkeep of our economies—which in turn necessitates the fantasy of an underclass. A ‘ship of fools’, the categorizing of people who ‘can’t keep up’… The Burnouts. As a way to fight back, I embrace these labels.

Maybe it is wisdom that after maniacally making the live tracks described above during the pandemic—alongside a few more side projects—now I am fortunate to have time to reflect, do this interview, to read (including No Fun), and go on my first trip in a while. We know that the world, the way it is economically set up, does not want to reward this modus of slowing down, not conforming to time and work pressures or compulsions to produce and consume.

Jess, may I ask why you decided to focus on a “band” rather than just yourself?

It’s a good question and one I need to answer in multi-fold. ‘Band of Burnouts’ is a research lab with the School of Commons, and when applying I realized it was a central motivation to collectivize the research on burnout that I had been doing in solitude during the pandemic (which was a depressing situation and topic to be dealing with on a daily basis, alone). After months of reading research papers, scientific studies, etc. whilst also speaking with and interviewing people who had also had a burnout, I noticed a massive gap between that former type of research and what I was more interested in—the personal stories and the details within those that bio-medicine, the field of psychology, etc. has not and is not accounting for.

It was a somewhat visceral act that came to me (undoubtedly through my own desires) to band together through this experience and form a fluid collective and sharing of experiences—as the experience of burnout can be very lonesome, disorienting, confusing, and make one feel like the ‘odd one out’ or like something is wrong with them. There is a lot of self-blame, guilt and shame associated with burnout and its social stigma, so to frame this work as a band of burnouts felt like a welcome take on all the other approaches I have seen. And admittedly, I love music and particularly 60s and 70s rock/psychedelia so that aesthetic has always spoken to me. I wanted to bounce off of the experience of being in a band, bonding over a commonality, and taking this into the less-typical space of research, artistic interventions, storytelling and sharing experiences—from the overall happening to those minute details.

This is Part One of a two-part interview. Continue to Part Two here.