Since 2016, (d)estructura has traveled to various locations, including Cuba, Colombia, Turkey, Italy, The Netherlands, Argentina, Chile, Switzerland, and Spain. The initiative asks diverse communities how they envision their lives in ten years and what they need to achieve those visions. Through a game focused on the collective construction of values and physical structures, (d)estructura aims to explore possible futures in contexts experiencing social, political, and economic transformations. The game's methodology combines negotiation, chance, and material construction, revealing both individual positions and group dynamics: what participants prioritize, what they discard, how decisions are made, and how shared resources are sustained. During their participation in the School of Commons (SoC) 2025, these questions became more pronounced as the team continued with the intention of opening up the game to be used by others beyond the direct participation of its creators. This effort confronted various ethical, political, and organizational tensions: How can collaboration be expanded without losing memory? How can emerging data be analyzed and communicated? How can the project's economy be sustained? How can non-ethical appropriation practices be avoided? How can the process be liberated from the desire for ownership? The virtual and in-person meetings at SoC revealed a symbolic convergence: the imagination of the future is rooted in community, sustainability, justice, care, equality, and an expansion toward the more-than-human. At this intersection of collective practice, ethical reflection, and the desire for shared futures, (d)estructura positions itself as a dynamic space for rethinking how we imagine, negotiate, and construct what is possible.

Common (d)estructuras

How can we envision a shared future? What common values allow us to imagine it together? What other elements, not typically considered "values," are necessary for this process? How can we reach agreements for the collective construction of a framework that reflects our individual and collective desires and visions?

(d)estructura was founded in 2016 in Cuba, initiated by the Colombian artists Juan Esteban Sandoval and Alejandro Vásquez Salinas (el puente_lab) along with Mariangela Aponte Núñez, in collaboration with Cuban curators Laura Salas Redondo and Erick González León, and Italian curator Cecilia Guida. From 2016 to 2019, (d)estructura traveled across various provinces of Cuba, exploring visions of the future through a game that began with the question: "How do you imagine your life in 10 years, and what do you need to achieve that vision?" This question was set against a backdrop of significant social, political, and economic changes in both Cuba and Colombia, including economic openings and crises, the death of Fidel Castro, and the signing of the peace accords between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP), among other notable milestones and historical shifts at the start of the 21st century.

What began as a question about the future, initially addressed by Cuban participants, also served as a catalyst for imagining futures in other contexts. How would this question be answered in Colombia, in other Latin American countries, in Europe, or in North America? As a result, in 2019, the game reached Cali and Medellín in Colombia, along with Istanbul in Turkey, Biella in Italy, The Netherlands and by 2025, it had expanded to Buenos Aires, Argentina; Santiago de Chile, Chile; Zurich, Switzerland; Barcelona, Spain; and once again, Biella, Italy.

Board Game Methodology

Los Hondones, Cuba, December 3rd, 2025

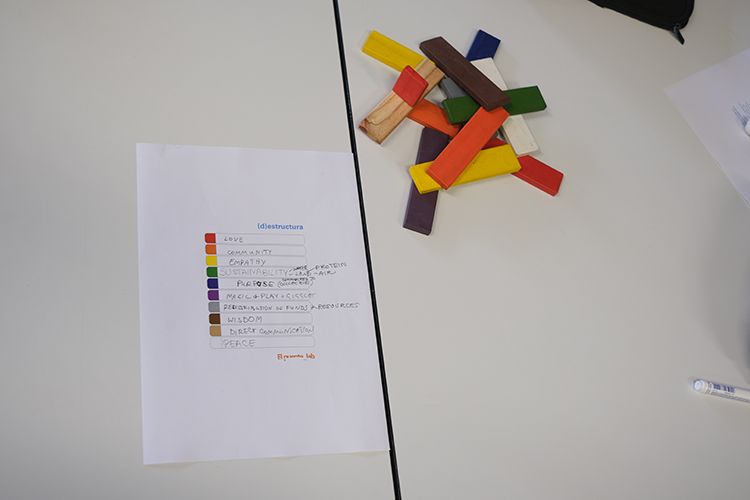

How to Play: The game begins with a minimum of 3 players and a maximum of 6 players seated around a table equipped with colored wooden pieces and a spinning top. Once the question is posed, the players collaborate to decide on 10 collective "values" that envision their future. Each of these values is assigned a color, corresponding to one of the 10 available colors.

As the game progresses, players must build the largest and most stable structure possible. The spinning top introduces an element of chance, as it determines whether players will add, remove, or replace pieces during their turns. Throughout the game, players consider important questions such as: What should be added, removed, or replaced? What does the structure need? What is missing? Which values are most important?

The game is facilitated by one or two people who introduce and explain the rules of the game and also have the role of observing the dynamics of the game to finally make a synthesis or interpretation of how the game unfolded, bringing out the main elements of the group’s dynamics and the personal positions of the players and their impact on the resulting (d)estructura. The analysis made by the facilitator/observer is an invitation to the players to reflect on how individual decisions impact the group dynamic and vice versa. At the end of the game, participants share their reflections, feelings, memories, and emotions, enriching the group experience.

SoC 2025

Over nearly a decade of organic development with various communities, (d)estructura began exploring ways to expand and "open up" the game in 2024, making it accessible to different contexts. In September of that year, during the 25th anniversary celebration of UNIDEE at Cittadellarte Fondazione Pistoletto in Biella, Italy, the three Colombian artists met with David Behar Perahia, a former UNIDEE resident and participant in SoC 2024. He proposed himself to become an "ambassador" of the game, implementing it with the communities he was collaborating with.

This invitation to broaden the shared vision of desirable futures quickly brought various challenges. Internal and external tensions surrounding the game began to surface. Key questions emerged: What are the collective, collaborative, participatory, and cooperative dimensions of (d)estructura? How should copyright/copyleft issues be addressed? How can we ensure the participation of the three artists as “authors” while including others? How can we gather and analyze the data generated from each game to provide a broader perspective on both the game itself and the communities involved? How can we effectively communicate this information?

With these questions in mind, (d)estructura’s participation in SoC 2025 was established within an ecosystem of initiatives focused on reflecting on the commons.

(d)estructura at the Kick-Off, April 11-13, 2025

At the beginning of April, we held the first (d)estructura presentation during the virtual Kick-Off. For this session, Alejandro and Mariangela aimed to pose the main question of the game. This initiative allowed the team to introduce, albeit remotely, a scenario for speculating on possible shared futures. To facilitate this discussion, four virtual rooms were organized where participants could meet for a few minutes to share and record their initial wishes. These ideas were collected on a Miro collective whiteboard, created as a communal repository for the entire development of SoC 2025. The groups expressed the following themes:

(d)estructura: How do you imagine your life in 10 years, and what do you need to achieve that vision?

Group 1: Stability, oranges, chickens, growing most of our food and sharing rent, no more war, good health, access to quality healthcare, artistic fulfillment, a post-money economy (no more funding applications or selling art), bartering, and universal income.

Group 2: No children, intergenerational exchange, rebuilding social infrastructure, a community-led alternative economy outside of capitalism, and the exchange of cultures and knowledge.

Group 3: Flexibility, resilience, bodies of water, diverse altitudes, trust, and service to life.

Group 4: Addressing current precarity as essential to rethinking this question, reframing the inquiry to identify what we do not want, which can help build a broader collective vision for the future.

In meetings with participants of varying ages, countries, and identities, a vision of the future emerged, marked by a desire for stability, community life, and a closer relationship with nature. Some participants imagined specific scenarios—such as growing their own food, raising chickens, or living among orange trees—while others focused on broader concepts like resilience, trust, or access to bodies of water. A common aspiration emerged across all groups: to move away from the logic of precarity and toward more humane economic models based on exchange, collaboration, and sufficiency.

For many, envisioning the future required first acknowledging the fragility of the present. Thus, redefining what they did not want became a necessary step to create space for new possibilities. There was also a shared desire to imagine renewed social structures where well-being does not rely solely on money, scholarships, or competition, but rather on solidarity networks, adaptable social infrastructure, and genuine dialogue between cultures and knowledge systems.

Though the visions varied from concrete images to more abstract reflections, they all converged on a singular horizon: a simpler, more conscious, and shared life. A future where community is the foundation, nature frames existence, and collective bargaining paves the way for building what is possible.

(d)estructura at the Annual Gathering – July 4th, 2025

Viaduktraum at ZHdK, July 4th, 2025

Three months after the Kick-Off, the opportunity to participate in person at the Annual Gathering finally arrived. With a tight schedule, activities began early in the morning. It was the first time the 2025 cohort was meeting face-to-face. People were filled with joy at the realization of the reality beyond the screens, eager to make the most of the limited time and space. What were we going to do?

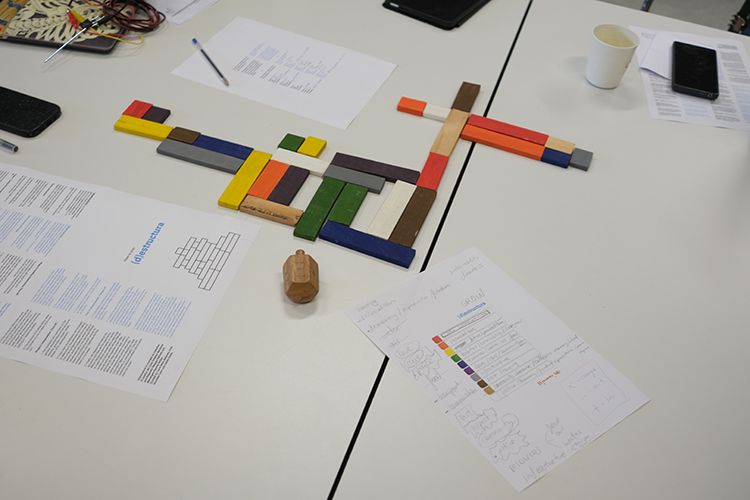

In this case, and given the travel costs, Mariangela traveled on behalf of the (d)estructura group. Juan had previously mailed some games for the presentation and as a donation to SoC. Mariangela had arrived from Cali, Colombia to Zurich, Switzerland at midnight on July 3rd, prepared to get things moving the next day. In the gathering room, three tables were set up for three games, along with three audiovisual recording setups.

The morning gained momentum with serious discussions about the future, bringing together people from diverse backgrounds, ages, contexts, languages, and perspectives. Fundamental questions were posed: How do we envision a desirable future? What does the concept of the commons mean to us? How do we imagine the future of the community of practice?

Three simultaneous games progressed at their usual pace. In some cases, the initial discussions took longer than expected, while other groups organized themselves swiftly. This highlights the human experience of decision-making: for some, each choice requires deep reflection, while for others, the game calls for spontaneity and quick thinking.

Being the one who facilitated and observed the game, Mariangela moved through space and observed the emergence of three structures from the SoC 2025 cohort. The challenge of organizing collectively is always significant in the game. While it may seem simple to arrange small colored pieces on a table based on individual and collective preferences, these small societies offer valuable insights into their organizational structures. Usually, chaos and order are created from an internal hierarchy of values that players establish through conversations, trial and error, consensus, or ultimately by urgency, as the time to organize is limited.

Throughout the game, the conversations took on remarkable depth and complexity. Each table was filled with laughter, engaging discussions, gestures of surprise, and perhaps a hint of adrenaline. Although the game is not competitive and there are no winners or losers, the shared experience in a specific time and space created an exhilarating atmosphere.

Applause and laughter erupted when one of the tables completed its (d)estructura, and the other two tables continued discussing and assembling until time ran out and they had to stop. The next instruction was to observe how the (d)estructuras were assembled, noting what was at the bottom and what was on top, how stable each structure was, and whether any or all of it represented the group and its members.

At this point, conversations became especially interesting. Individual and collective surprises emerged as participants reflected on their decision-making processes. Discussions revolved around the negotiations over what was considered important, who defended various values, which values were given less attention, and ultimately revealed the internal (d)estructuras that each person held.

Table #1, Zurich, July 4th, 2025.

Red: open imagination

Orange: recreation

Yellow: future speculation

Green: habitat (sustainability / cleanness)

Blue: resources (water/air/food)

Purple: love / care / community

Grey: infrastructure

Brown: rest / housing

Wood: community archive / collective memory / ritual

White: justice (democracy / freedom / representation / peace / respect)

The initial decisions regarding the values involved lengthy discussions and negotiations. The brainstorming and value-imagining processes, often grouped into clusters, can be observed in the data sheet. After that, the game flowed very smoothly. The participants in this group recognized the challenge of constructing the "largest and most stable possible" structure by expanding horizontally, with the understanding that no value is inferior or superior to another. This creates a challenge in establishing "hierarchies," which is precisely the intriguing aspect to explore. What motivates the involved individuals to avoid vertical growth? Where does the structure begin and end, and from what perspective? I believe the shared space serves as a canvas for creativity and imagination on the horizon.

Table #2, Zurich, July 4th, 2025.

Red: love

Orange: community

Yellow: empathy

Green: sustainability (water / land / air / protein)

Blue: purpose (connected to collective)

Purple: magic + play + giggle

Grey: redistribution of funds and resources

Brown: wisdom

Wood: direct communication

White: peace

For this group, assigning values was a quick task. However, making decisions based on chance took longer. Initially, the group aimed to create a "star" shape instead of a square. Throughout the game, the structure evolved and became less traditional—neither wide nor tall, but rather entropic. By the end of the game, many pieces remained unintegrated. While most of the large pieces of each color were incorporated, far fewer of the medium and small pieces were, as shown in the image.

The Tables' Assembly

Table #3, Zurich, July 4th, 2025.

Red: heart intelligence

Orange: innovation

Yellow: play

Green: sustainability

Blue: flexibility

Purple: care

Grey: learning

Brown: non-hierarchical organization

Wood: non-human centric / more than human awareness advocacy

White: equality – intergenerationality

The initial decisions, as well as the development of this game, followed a pace between the first and the second, neither fast nor slow. This group carefully considered the color and arrangement of each piece. Every piece was strategically placed, creating a well-balanced structure that harmonized the width of the base with its height. The pieces were primarily assembled horizontally, making the structure quite stable. However, by the end of the game, a few pieces still needed to be integrated. This can be observed in the image: one medium-sized piece and one small piece in gray and blue, along with one small piece in brown, red, orange, and wood.

What transpired at the second meeting was more than just an exercise in assigning values to colors; it was a collective exploration of priorities, desires, and shared understandings of life. Although each table worked independently, the results converged almost organically, as if all three had been guided by a common ground. The colors reflected this collective thinking: affection, sustainability, and community emerged repeatedly, supported by values that were emphasized—care, empathy, justice, and equality.

It is noteworthy that "human" was not seen as a fixed center but as something that expands toward the more-than-human. For example, wood was associated with direct communication, ritual memory, and an enhanced awareness of other life forms. Similarly, brown—sometimes representing wisdom, sometimes rest, and sometimes non-hierarchical organization—demonstrated that solidity does not have to be rigid and can be sustained through collective learning.

The consistent presence of green at all three tables, always linked to sustainability, highlights a shared concern: life can only be envisioned if there is an environment that can support it. A similar pattern emerged with white, which consistently represented ethical values such as peace, justice, equality, respect, and representation. This convergence does not appear to be coincidental; instead, it indicates a profound agreement on the essential foundations for inhabiting the future.

Collectively, the colors from the second gathering illustrate a vision that combines emotional sensitivity, community care, ecological awareness, and a strong ethical foundation. They not only reveal the value assigned to each color but also signify the kind of world the participants wish to create and the values that make such a world possible.

Observing and reading between the interstices of the players’ actions and the words spoken throughout the game, and then interpreting the resulting tensions into a collective vision, meant that the role as facilitator is an indispensable part of the mechanism that made the game meaningful. Observation and interpretation lie at the heart of what the game can offer in a collective discussion, among the personal experiences that emerge from those who take part. The facilitator begins as a passive observer but becomes active in drawing out and condensing the shared visions of the future that emerge. These interpretations, which we are now able to make—and which we as a collective have learned to make playing the game in different contexts—have been refined through ten years of experience. This is perhaps one of the important elements to define when the game becomes something that its creators are no longer part of. It is not just about communicating the game rules and providing materials to build a set; it is about transmitting an approach of observation and facilitation for a collective process.

Between the Kick-Off and the Annual Gathering

During both events—one conducted through virtual rooms and the other through in-person gaming—a crucial point of convergence emerged: envisioning the future is not just an individual endeavor, but a deeply collective act. Although the formats and dynamics varied, participants consistently returned to the same symbolic themes: community, sustainability, care, and the necessity to rebuild fairer social structures.

In the first event, these desires were expressed as aspirations: stability, alternative economies, trust, and simple living. In the second event, these same ideals were represented by colors associated with values: empathy, sustainability, justice, equality, care, infrastructure, and collective memory. While the language changed, the underlying concerns remained consistent.

Both gatherings reveal a clear pattern: to envision the future, we must examine the present, identify what is lacking, and design new ways of living together. The phrases shared on Zoom and the color associations at the table reflect the same drive: to create worlds where life—both human and non-human—can thrive without precariousness, loneliness, or rigid hierarchies. A shared vision emerges: a future built on common ground, guided by ethical and emotional values, and structured around cooperation and mutual responsibility.

Inside (d)estructura

So far, the game has maintained its usual rhythm while discovering other groups that, alongside it, imagine new possibilities. However, the questions motivating (d)estructura's participation in SoC 2025 remain open:

- How can we expand the possibilities for participation, collaboration, cooperation, and co-creation within the current state of the (d)estructura game?

- In what ways can we collect the information that emerges during games, and how can we conduct sensitive analysis and create visualizations to understand that data?

- How might the development of virtual and physical platforms enhance exploration and narratives for (d)estructura?

- What potential challenges could arise when attempting to broaden the range of participation in the project?

Complexity reaches beyond mere discussion and written word; it emerges powerfully in the real-world arena of collective bargaining. This situation calls for delicate and profound negotiation. The SoC experience has unlocked the potential to formulate both internal and external, individual and collective questions, explore possibilities, and assert our critical positions with conviction.

The decision to "open up" the game inspired participation in SoC, aiming to think collectively alongside other initiatives. This openness also sparked conversations among us who initiated this process nearly a decade ago—conversations that sometimes reveal opposing views, similar to the dynamics in games themselves. Although these conversations have not reached, until now, the level of depth they perhaps required, this time at SoC has triggered the need to respond to them as an imperative condition for the continuation of the project itself.

This raises questions that touch on both technical and ethical aspects:

1. If the game is "released" for others to activate in various communities, how can we follow these activations? How can we collect, process, and visualize this information?

2. Can a web platform be a viable tool for gathering these experiences? If so, what level of participation could it facilitate?

3. How can we ensure this project is economically sustainable for everyone involved?

4. How can we prevent opportunism from arising around a shared idea?

5. Finally, how can we free ourselves from the need to own?

The participation of (d)estructura during SoC 2025 has primarily fallen on Mariangela, one of the initiators. As we navigate "adding, removing, and replacing" at the core of the project, we find ourselves limited in making decisions about something we are deeply involved with and whose history is intertwined with ours. We had engaged in conversations where, among several other ideas, the question of patenting the game emerged, which is non-negotiable for us. Politically and creatively, we do not see copyright or patents as compatible with the spirit of this project.

Although this process has not begun yet, one of the possibilities we have been imagining for the future of the game is the creation of a digital space where everything that happens after each play session can live on. Rather than simply recording outcomes, this platform would allow us to see how people intuitively connect colors with values, how different generations approach the values placed on the table, and how certain ideas—such as ecology, health, or love—appear and transform across different contexts. All of these could be compiled into a book or a publication.

Over time, this shared space could reveal the unique shapes, arrangements, and visual languages that emerge each time the game is played, offering new ways of reading and understanding those encounters. It could also become a kind of living map, showing where (d)estructura has been played around the world and highlighting the values that resonate most strongly in each place.

On the other hand, the creators are still exploring how to offer a physical version of the game for public use.

Imagining possible futures—futures founded on organizations grounded in shared values—requires open methodologies and materials that are adaptable without erasing the histories or legacies of those involved. For us, “opening up” the process is not an exercise of power or control; it is about creating common ground to nurture possibilities in a post-pandemic context marked by wars and social, economic, political, and ecological crises, along with the rise of technological monopolies and systematic (and often violent) restrictions on community participation. We also face an ever-widening gap between the rich and the poor, especially between the Global North and Global South.

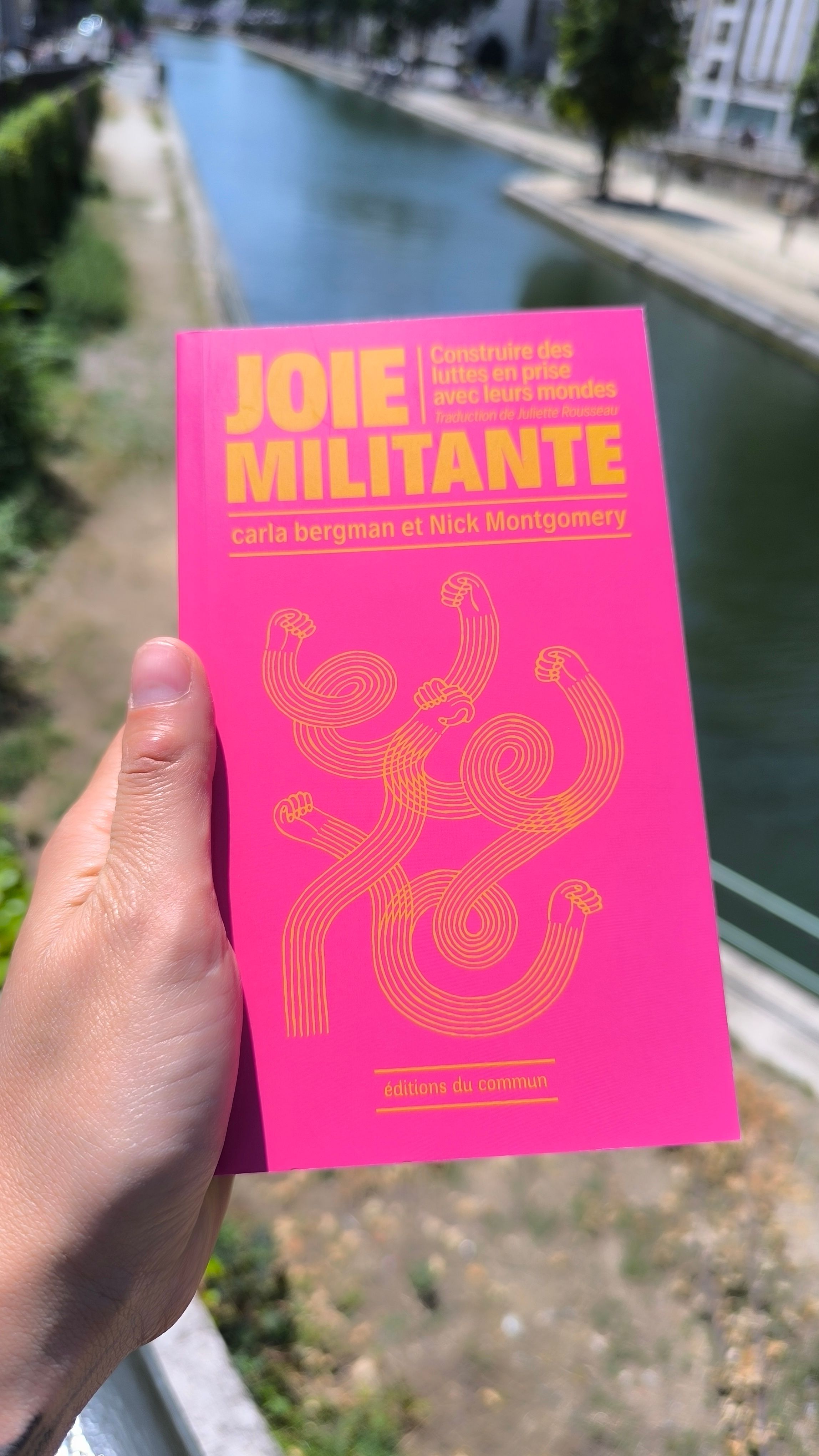

This year, the SoC platform has been more than just an inspiration; it has acted as a sea for challenging questions. Navigating the Ways of Working methodological website led us to the book The Militancy of Joy by Bergman & Montgomery. In their reading of Spinoza, I discovered the idea of joy and also playfulness as the ability to create new causes with others—an increase in the power to affect and be affected. This text has profoundly reshaped our understanding not only of the creative project but of every facet of our lifes. Isn’t that what we strive for whenever we engage with (d)estructuring or inhabit any moment of existence?

“The space beyond fixed and established orders, structures, and morals is not one of disorder; it is a space of emergent orders, values, and forms of life,” as noted by bergman and Montgomery (2017). They later state, “Joyful Militancy is a fierce commitment to emergent forms of life in the cracks of Empire, along with the values, responsibilities, and questions that sustain them.”

This book led us to bell hooks’s The Will to Change, and today Mariangela wonder if this intrinsic need to open up possibilities in (d)estructura is also a feminist imperative: the potential for envisioning a feminist future. As bell hooks (2021) argues, a vision of change requires us to imagine a world where relationships are not governed by hierarchies, violence, or emotional repression, but by solidarity, empathy, and reciprocity.

Alongside this methodological framework, there is also the affective network created by the projects and the human and more-than-human beings that enable them. The resonance of shared motivations and concerns through the self-organized program in SoC has provided a refuge for believing in the collective imagination of possible futures. This includes not only the capacity to recognize, care for, and support one another, but also the opportunity to collaborate with the team that sustains a school of the commons amid the political and economic crises affecting culture locally and globally.

Almost ten years ago, when we envisioned (d)estructura, what mattered most to us—and continues to matter—is this sense of urgency: How do we imagine revolution and transformation today? How do we reorganize ourselves for tomorrow? How do we support each other in conflict?

For us, (d)estructura is more than an artistic project through playfulness; it represents living activism in every emergency. We’ve always known that the game becomes effective precisely when it “doesn’t work”—when it doesn’t lead to hierarchical structures, when its rules are questioned, or even disobeyed. Ultimately, emerging (d)estructuras are less about visible or physical forms and more about internal ones: those that are activated when we engage our own value systems in the space of the common.

The layers of analysis that emerge in each activation create extended cartographies of desires, commonalities, contrasts, and tensions. Yet, each encounter adds complexity. Each engagement redefines the values we strive to uphold, and sometimes, analytical effort can feel elusive, especially amid divergences and the boats that stray off course.

- But how are we going to analyze all this?

We still don´t have a definitive answer, because for the moment what intrigues us it is the very possibility of observation.

- What if someone appropriates this idea?

We wonder, does the future belong only to a select few? Isn't that what, in the words of Bergman & Montgomery, the Empire has led us to believe-that we have no agency over our futures because they have already been designed by others? Shouldn't the future be an active re-appropriation of our lives in the present?

- And what about all the data we collect in the games?

We deeply question: Aren't data, as a commodity, just another form of control wielded by the BigTech today? Who owns the information about individual and collective desires and needs? Shouldn't we actively reclaim the agency we have over this imagination/information? How can we create meaningful connections for transformation that are sustainable but also maintain a critical stance toward the exploitation of individual and collective information? And above all, how can we remind ourselves today that we are more than just data to train AIs?

This game originated in Cuba in 2016, a time when internet access and information were heavily restricted. One hour of mobile internet cost two dollars, which was unaffordable for many Cubans. Fast forward ten years, and the situation has dramatically changed. Smartphones, network connections, and systems for generating information are now nearly ubiquitous worldwide. People share their desires and needs daily on social media. Artificial intelligence models are trained continuously by thousands, even millions, of people, both consciously and unconsciously.

Never before has so much human-generated information been so centralized, controlled, and monitored. Never before has there been a system capable of predicting future trends based on globally collected information. Despite this advancement, we firmly believe in the fundamental human need for face-to-face interaction in negotiations. Understanding our own desires, needs, and limitations is crucial for comprehending those of others. We believe that the potential for genuine encounters remains irreplaceable. This is perhaps what keeps (d)estructura a relevant and essential game today. Let’s play together!

Do we have answers for the future? We barely have a handful of present desires and needs for a vessel in the air.

Joie Militante by édition du commun

References

Aponte, M., Espinosa, M., González, E., Guida, C., Redondo, L., Sandoval, J., Vásquez, A., Venturi, R. (2018). (d)estructura. Viaindustriae Publishing.

bergman, C., & Montgomery, N. (2017). Joyful militancy: Building thriving resistance in toxic times. AK Press.

hooks, b. (2021). El deseo de cambiar: Hombres, masculinidad y amor (J. Sáez del Álamo, Trad.). Bellaterra.

Juan Sandoval

As an Artist, he has exhibited internationally since 1994.He is co-founder of the collective El puente_lab in Medellín, Colombia, a free lance artist and teacher.

Alejandro Vasquez Salinas

Medellin 1979. Master of Fine Arts, Utrecht School of Arts,The Netherlands. He is currently Director of the Paul Bardwell Gallery of Contemporary Art at the Centro Colombo Americano and is in charge of the Deseartepaz program of the same institution.

Mariangela Aponte Núñez

Mariangela is a Colombian transdisciplinary artist whose work merges craft, electronics, and collective practices. She explores the art-body-life link through yoga and organic materials.