What happens when we treat radio not as a technology to command, but as a living field that gathers us into relation? We consider radio primarily as a cosmic force, moving through bodies, landscapes, and infrastructures. While states divide the radio spectrum into neat parcels of ownership and control, radio itself remains radically ungovernable: it leaks across borders, diffracts off the ionosphere, and echoes with the Big Bang.

Through our collaborative practice of building improvised radio receivers from scrap materials, we listen collectively to a fusion of natural emissions and human transmissions. These open, untuned devices invite a mode of attention rooted in uncertainty and curiosity, revealing layers where local broadcasts, cosmic hiss, and electrical disturbances coexist. In these gatherings, radio becomes not a tool to be mastered but a companion in shared experimentation, learning, and attunement.

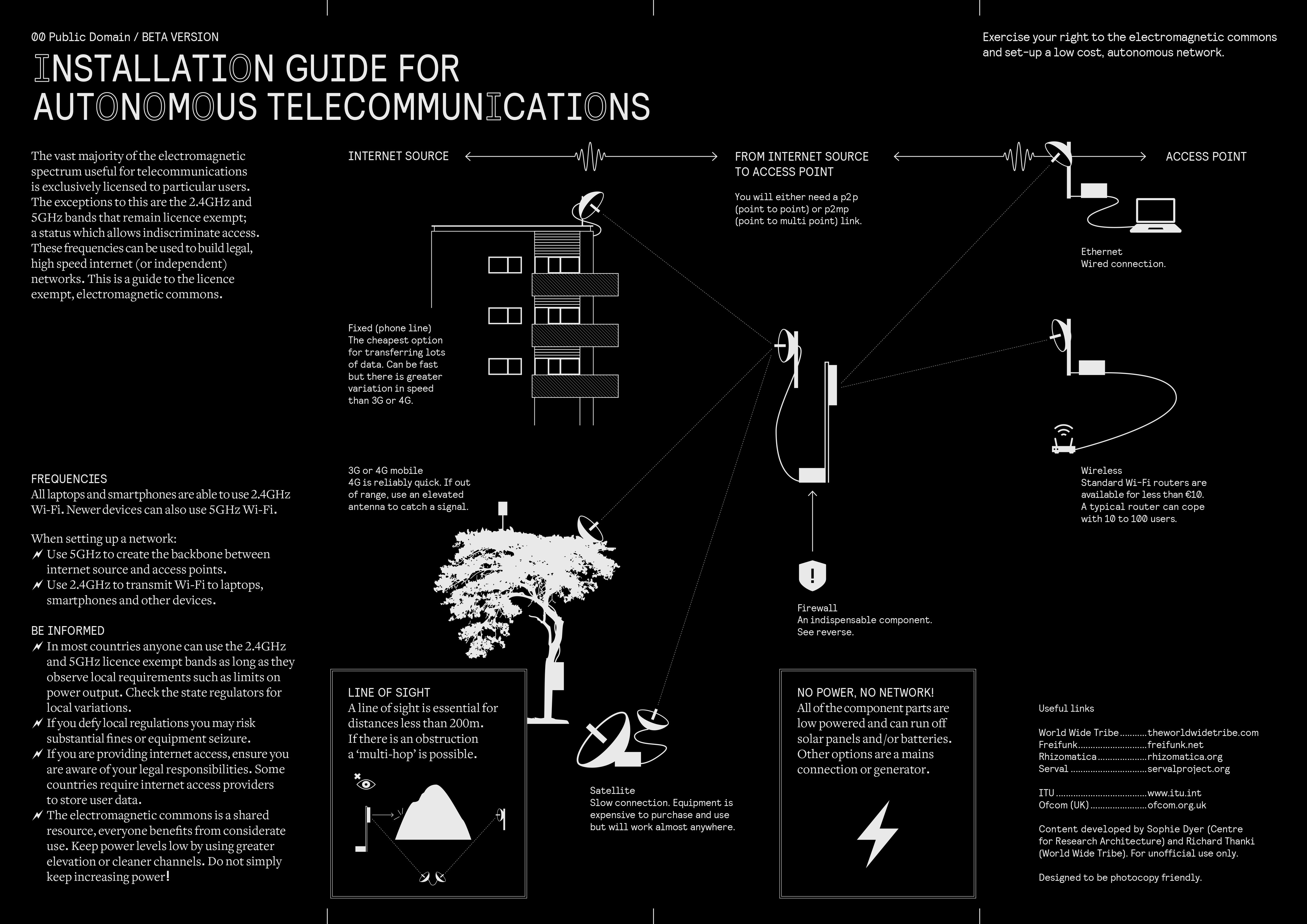

Drawing from Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (1988), we imagine a ‘Carrier Bag Theory of Radio’: in which receptacles for radio (receiving devices that allow us to listen) are valued over the ‘long, hard objects’ (Le Guin, 2024, p.28) of transmitting antennas. We understand reception as a continuum that vastly and importantly predates modern technological transmission, and we see the radio spectrum as a collective vessel of forces rather than a territory to be claimed. We align this thinking with calls from artists Celeste Oram (2024) and Soph Dyer (2017) for an electromagnetic commons, reminding us that radio governance is always cultural, political, and, for us, embodied.

This text offers a poetic reorientation toward listening and dreaming -together, openly, and within the ever-shifting electromagnetic field that surrounds us.