This project focuses on how to effectively visualise environmental science data through colours for climate communication, in a shared open and equitable manner. Thus, our primary objective is to use colour visualization to make climate information as clear, simple, and accessible as possible, with the focus on helping the groups most affected by the climate crisis to understand it and overcome the barriers they face. The project follows three research trajectories.

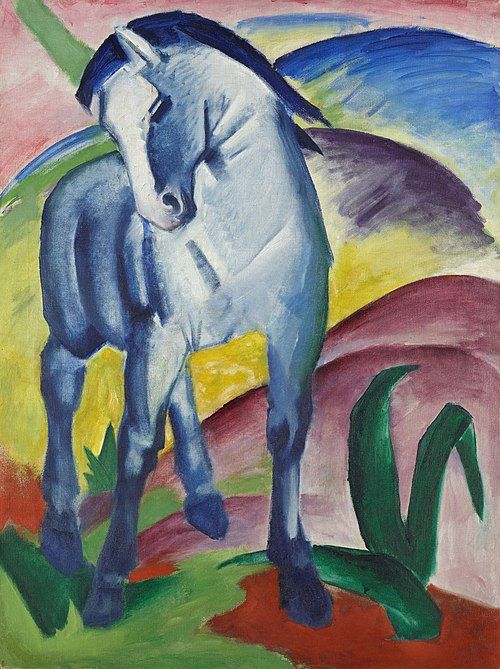

1. Colour is closely linked to human emotion.

As an integral aspect of both natural and constructed environments, colour carries aesthetic appeal, with certain colours being perceived as more pleasant than others. Further research shows that humans systematically and reliably associate colours with emotions (Jonauskaite et al., 2025). Precisely because colour possesses this power to transcend language and access perception and emotion directly, this project employs colour as the core element to design visual tools that move beyond the limitations of text and graphs. This approach aims to break through the traditional barriers of climate communication, trigger emotional responses, and thereby deepen public engagement with climate issues.

2. Inclusive dialogue through colour.

An inclusive engagement must specifically prioritise communities most vulnerable to the climate crisis, as its impacts disproportionately affect marginalised groups. Their vulnerability stems from intersecting factors such as geographic location, financial and socio-economic status, cultural and social conditions, limited access to resources and services, and restricted decision-making power (World Bank, 2025). Therefore, effective design must overcome these very barriers. As noted by the Chinese writer Bi Feiyu, color constitutes a form of social equality in the world of the sighted (Bi, 2016). It serves as a foundational, low-barrier visual language that can transcend socio-economic divides, making it an ideal medium to initiate inclusive dialogue and co-design processes.

3. From perceptual equality to universal access: designing beyond sight

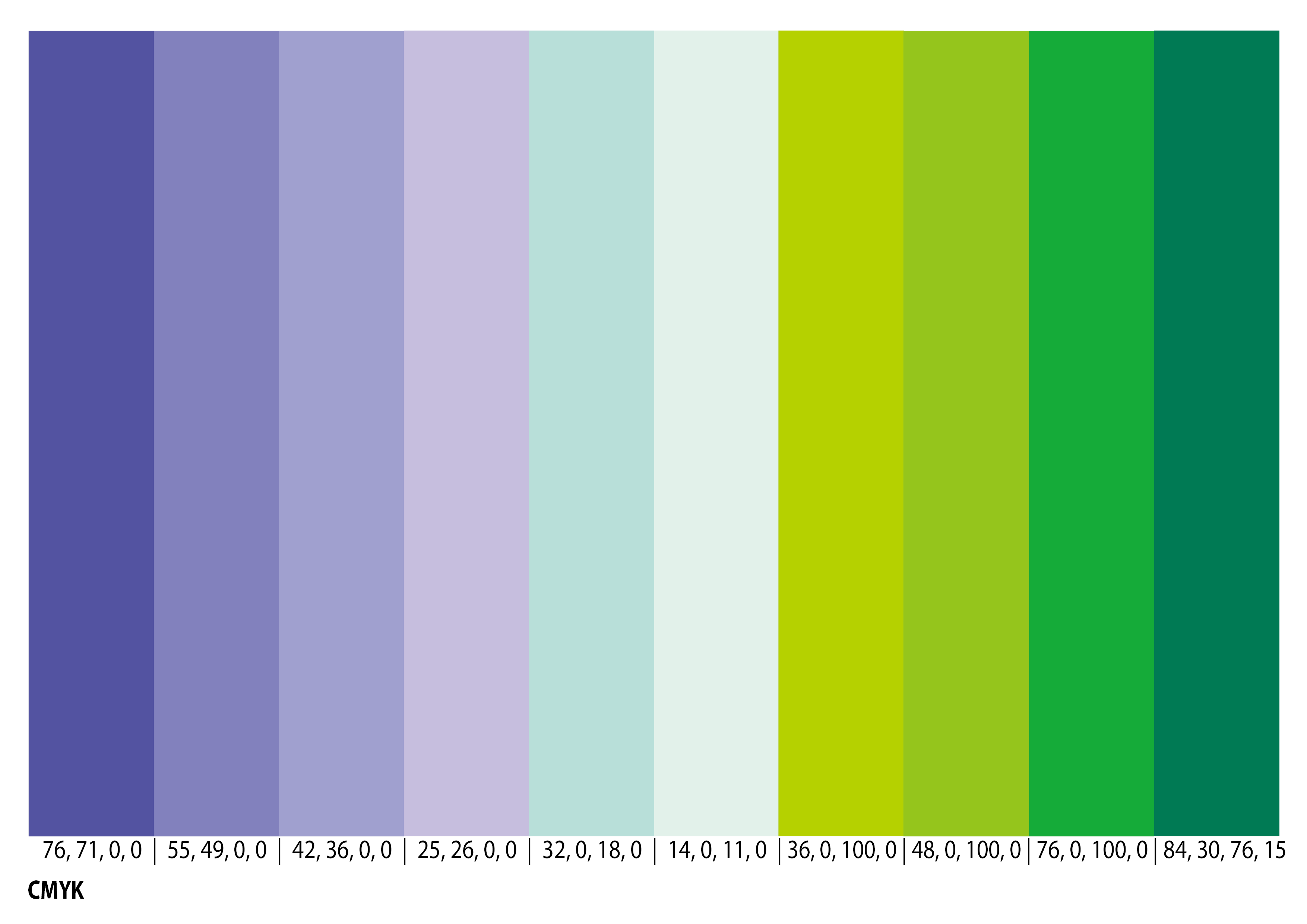

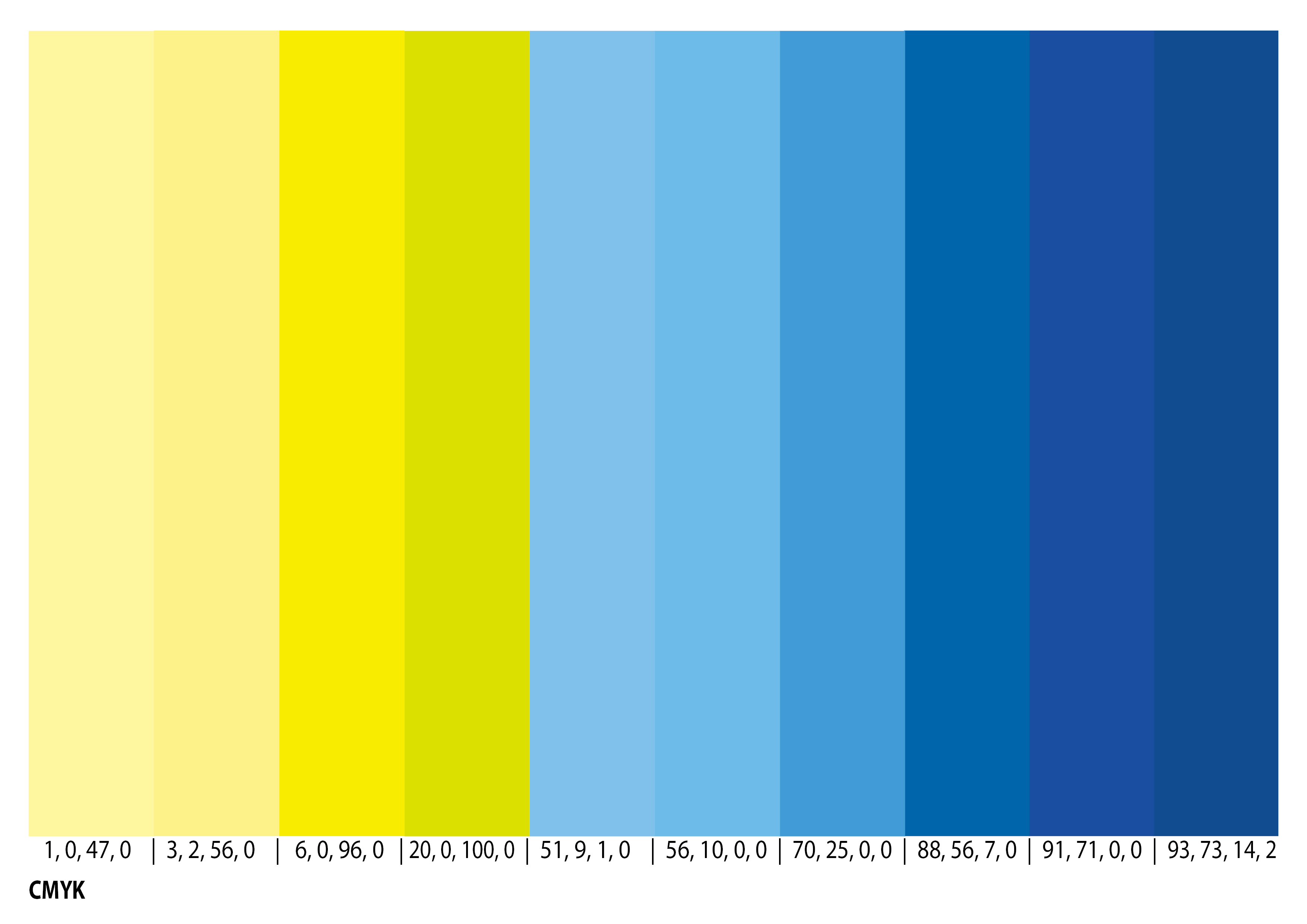

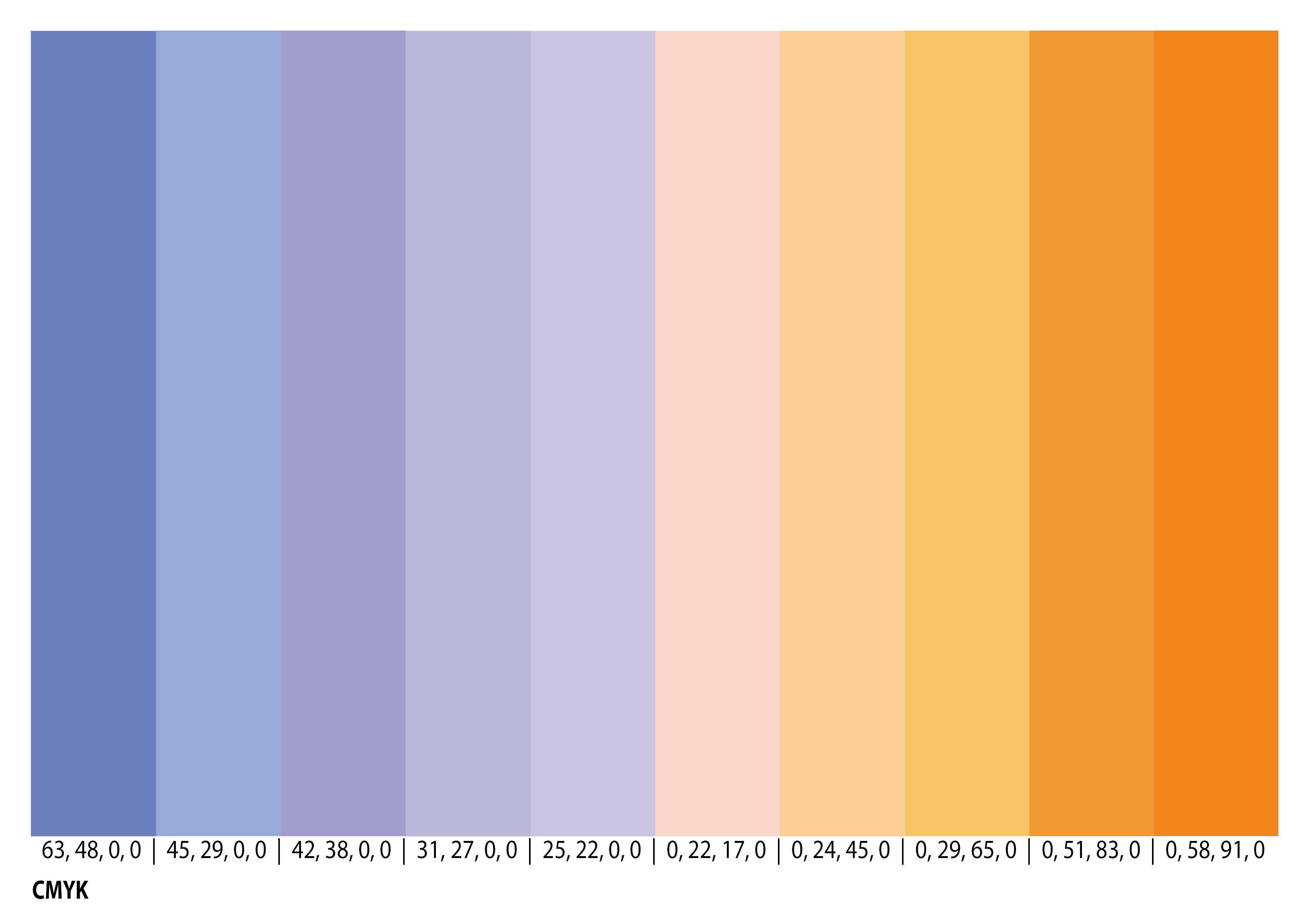

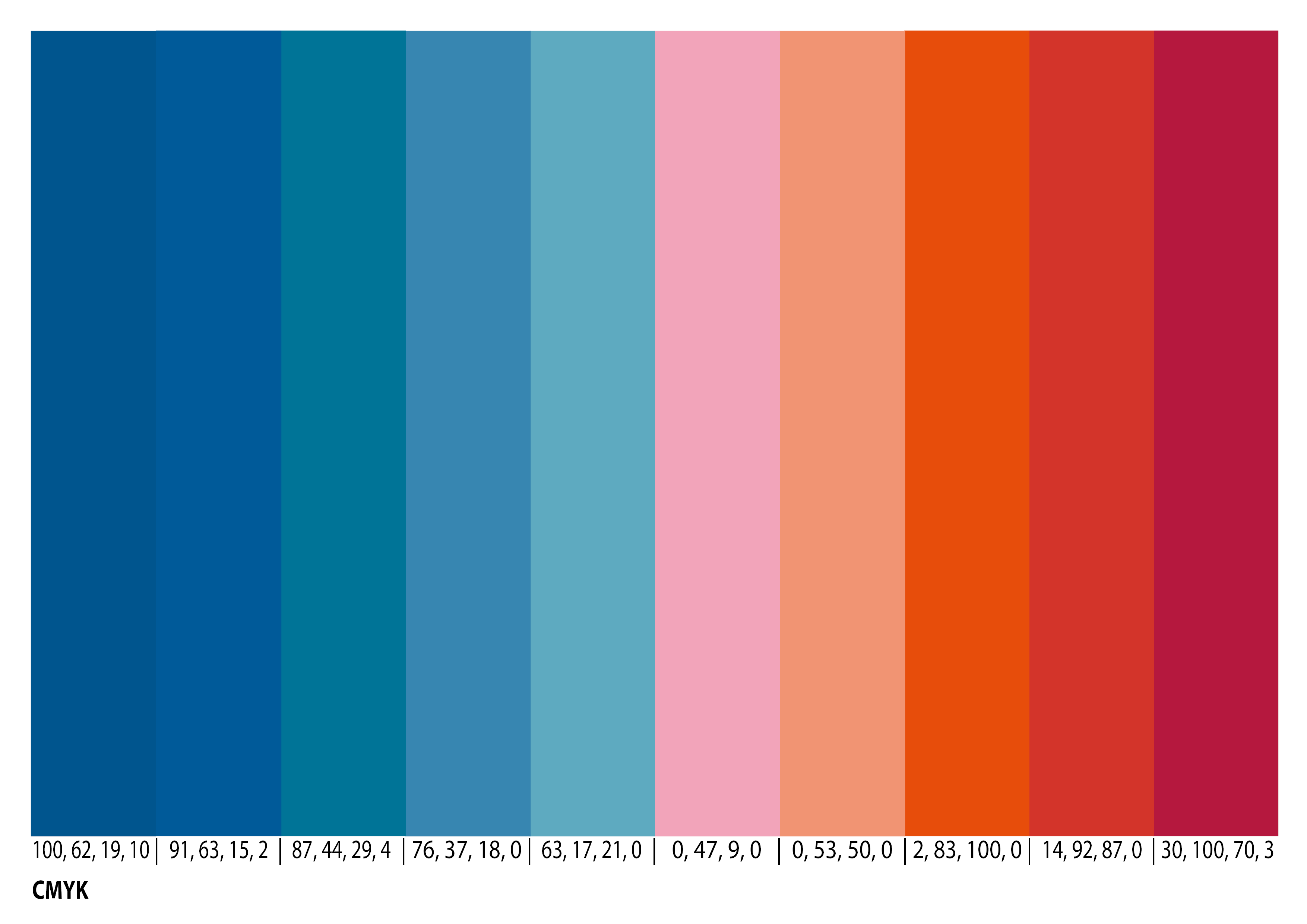

If colour is to serve as a truly equitable medium for inclusive dialogue, then the design must actively extend its principles of accessibility to include those with diverse visual abilities. This commitment to universal access necessitates translating the concept of inclusion into concrete, physiological design standards. Therefore, all colours in our visual system were selected and tested to be clearly distinguishable for individuals with common forms of colour vision deficiency, such as red-green or tritanopia colour blindness. Furthermore, to ensure the system's reliability and broad utility across both digital and physical mediums, CMYK colour codes were strictly specified for all selections. This guarantees consistent reproduction in print and facilitates the wider adoption of the visual system.

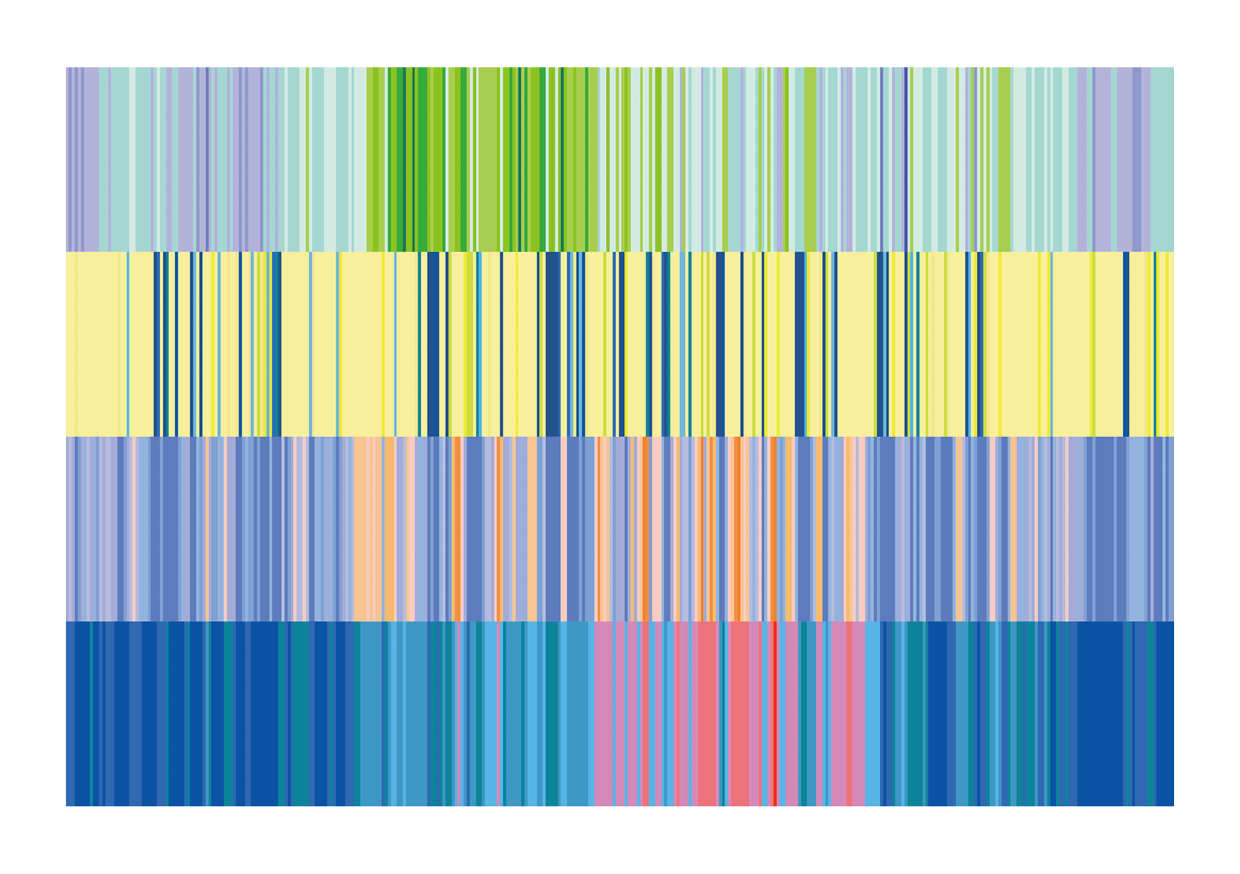

Methodology: translating flux data into an accessible visual language.

The scientists of the ETH Zürich Grassland Sciences Group have done excellent work in measuring fluxes, directly and continuously quantifying the net exchange of CO₂ between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere using the eddy covariance technique, amassing rich long-term datasets. In addition, meteorological data like air temperature, precipitation and the dryness of air (vapor pressure deficit, VPD) was measured in parallel, since these climate variables are considered important drivers of the CO₂ flux.. Now, our core challenge is to select colours that can transform vast, abstract flux data into visuals which the public can grasp and connect with. This involves a deliberate choice of colours based on three key criteria: i) their accessibility for colour-blind viewers, ii) their inherent emotional resonance, and iii) their ability to convey meaning across cultural barriers. Guided by these criteria, our final approach is to visualise each CO₂ flux or climate variable using a pair of contrasting hues to represent an opposing process or condition.